Call it a modern take on the museum, or an immersive, titillating, audiovisual experience. Whatever you call it, Fabrique des Lumières is an experience about art. It’s created to excite, to incite, and to overwhelm. It’s one of a kind, but available to all. Fabrique des Lumières brings art to life: the works of the biggest artists in history, dished up in an ode of digital image and sound.

With these words, the exhibition Hollandse Meesters in Amsterdam’s Westerpark is described. Under the name Fabrique des Lumières, an old factory hall of the Westergasfabriek is transformed into an immersive experience featuring the paintings of Vermeer, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, and Mondrian. The result evokes mixed feelings: the immersion in the artworks undeniably works, but it also raises questions about what this audiovisual total experience does to art and our senses. In this blog post, we share our account of when we, three Makebelief researchers, visited the Hollandse Meesters exhibition at Fabrique des Lumières.

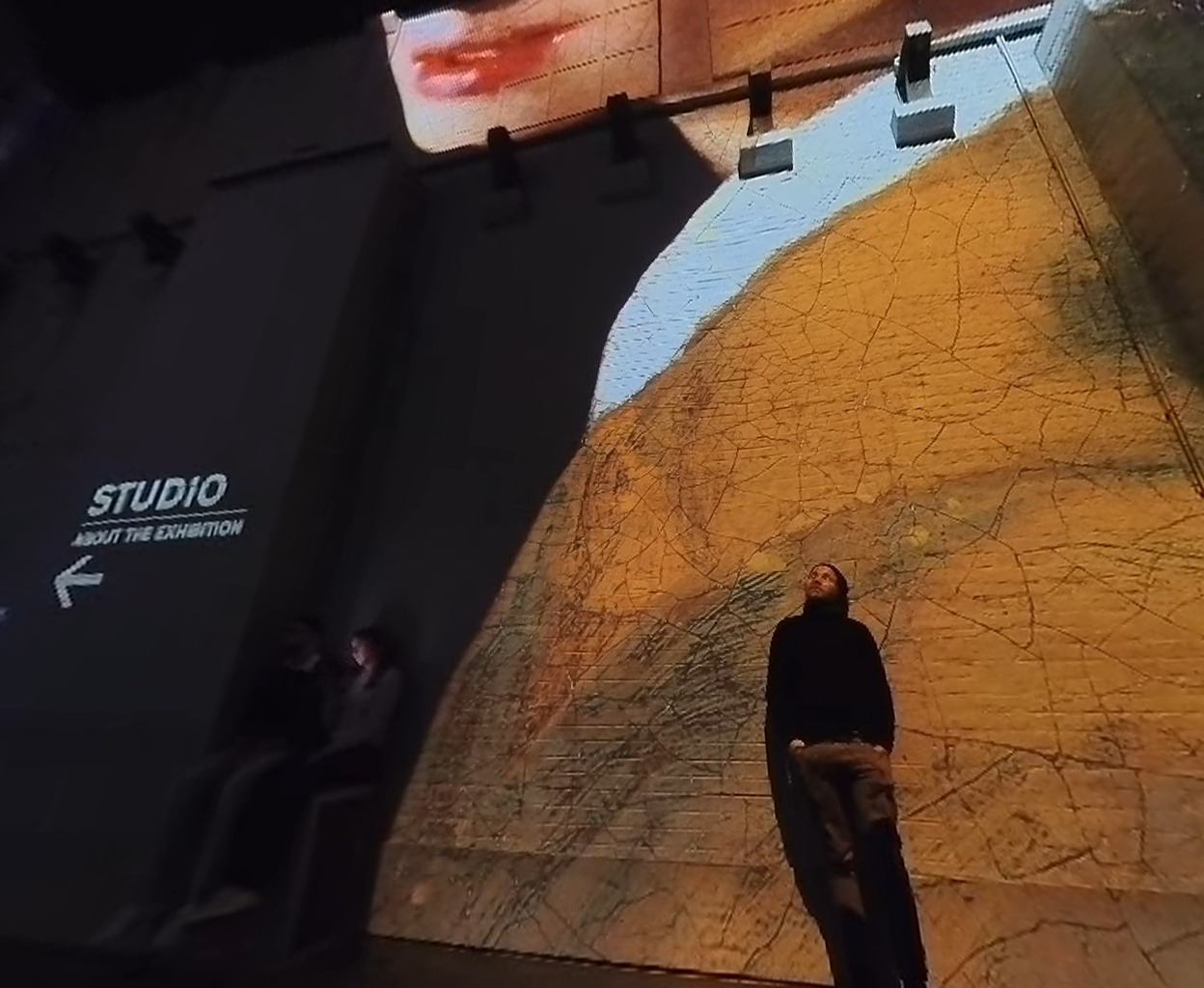

Upon entering, we step into a large industrial hall. The hall is perhaps ten meters high and thirty meters deep, with remnants of steam engines or generators scattered here and there. Then, the audiovisual total experience begins. The entire space is filled with moving projections. Paintings appear, immensely magnified, all around us. The room also fills with sound—immersive music enhances the effect of the projections. Classical compositions, such as piano pieces by Sibelius and Philip Glass, as well as jazz and (pop) music from Radiohead and Sigur Rós, underscore the emotions that the paintings of Vermeer, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, and Mondrian are meant to evoke. The paintings are stretched and fragments move throughout the space, over the walls, floors, and ceiling. With Van Gogh's Starry Night, the stars tumble through the room; with The Night Watch, the guards march across the towering walls, accompanied by ominous music. Mondrian's abstract paintings light up the space to the bouncing sounds of bebop. In Van Gogh's Wheatfield with Crows and his infamous Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, Nina Simone's Feeling Good resonates through the space. By clicking on the YouTube video below, you can get a sense of what it's like to be in this space. The video is shot in 360-degree format, allowing you to look around by moving your phone or dragging with your cursor.

For us, the effect was a calming sensation. It’s striking how freely people move around the space—some have laid down in a corner, others lean against the wall or sit back-to-back on the floor. This is an advantage of this form of exhibition that we hadn’t fully considered before. When the artworks are stretched out and projected all around us, you can be present everywhere, look anywhere, and feel free to be wherever you like. This stands in stark contrast to the classic museum experience, where the artwork typically hangs on a wall, behind a velvet rope, with the audience crowding around it. The pieces shown here are especially popular masterpieces that are often surrounded by throngs of people. Compared to how art is experienced in the Van Gogh Museum or the Rijksmuseum, we can imagine that this audiovisual total experience provides a liberating sense of hanging out in art.

Yet, critical thoughts also arise. It is striking how much the immersive format prioritizes effect over information. The artwork is barely contextualized. There is no explanation of how Vermeer was a groundbreaking force in his time, what makes Rembrandt's paintings so remarkable, or how Mondrian's abstract squares emerged from a rebellious artistic development that speaks volumes about the 20th century. Instead of explaining why this art is beautiful or significant, the format seems solely focused on imprinting on our senses that it is beautiful. To borrow from Birgit Meyer, it creates a wow-feeling. And I only need to glance at the goosebumps on my arms to know that the technology is very effective at achieving this.

Slowly, the thought creeps up on us that this "wow" feeling actually has little to do with the artworks themselves. The visitor is not told when or why the piece was created, or even the actual size of the artwork. In fact, the artwork is pulled apart in this immersive experience; artworks blend into each other, and fragments become part of animations. Afterward, we tried to reconstruct how the paintings were pieced together using the catalog, and it was often unclear what the individual artworks even looked like. Perhaps this is considered assumed knowledge, and the immersive art experience offers an emotional deepening of pre-existing knowledge? Yet still, at times it seemed as if the artwork itself disappeared from sight amidst the audio-visual spectacle.

In any case, this type of immersive art is not the place for critical engagement with art. For instance, this exhibition does not touch on the darker aspects of the Dutch Golden Age during which Rembrandt painted, nor does it explore the provocative dimensions of Mondrian’s work. The format itself seems to preclude this: when the art surrounds you, engaging all your senses, there’s no space for plaques or audio guides to provide context. Including such elements might disrupt the feeling of immersion.

It is also clear that this is a different kind of place than a museum. In contrast to, for example, the Rijksmuseum or the Mauritshuis, where most paintings by Rembrandt and Vermeer are displayed, this is not a recognized and subsidized (national) museum. While museums often have extensive educational objectives supported by foundations with ANBI status, this experience is a place where art can be approached more freely, and the impact on the audience can be maximized in a different way. Unlike the Rijksmuseum, which in recent years has invested significantly in contextualizing the Golden Age, for instance by emphasizing its relationship to colonialism and slavery, at Fabrique des Lumières the focus is on the feel-good effect. This is a company that justifies the ticket price of 18 euros with the promise of an unforgettable experience.

Immersive total experiences, such as those offered by Fabrique des Lumières, raise an interesting set of questions. Who determines the emotional value of art? Additionally, what role do projectors, surround sound, and immense spaces play in shaping our emotions? What room does this kind of "imagineering" of our emotions leave for critical reflection? And ultimately, what is the essence of art about? Is it immersive immersion in an aesthetic experience, or is it critical reflection and distance? How do emotional immersion and critical thinking actually relate to each other? Do they exclude one another, or can they be combined?

We plan to explore these questions further in our research on immersive experiences, especially when considering political uses of projection techniques. Whether dealing with national identity, religious persuasion, or cultural heritage, questions about diverse perspectives and critical engagement are crucial. As immersive experiences are deployed in more and more contexts, literacy about how and to what degree our senses can be programmed is increasingly important.

What we do know is that the technology is effective. Despite these critical observations, the exhibition made an impression. Blinking into the sunlight at Westerpark after leaving, it felt as though our senses had been on vacation.