Ernst van den Hemel

I am standing in a narrow concrete tube, 50 centimeters wide and 1.8 meters high. I have to hunch over a bit to walk through the tunnel. Around me, I hear the muffled sounds of bombings and explosions. It's a tunnel like those under the Gaza Strip, except this one is in a truck parked at Spui Square in Amsterdam. Inside a 20-meter-long trailer, a replica has been built of what the initiators call a ‘Hamas tunnel.’ On the outside of the truck, it reads: ‘How do we get out of here?’

The mobile installation is based on an artwork by Israeli artist Roni Levavi. Rachel Meijler, after losing her cousin during the attacks in October 2023, took the initiative to recreate this artwork in the Netherlands. With financial and practical support from, among others, the Christian Zionist foundation Christians for Israel, Dutch volunteers built the tunnel, which has been traveling across the country since 2024.

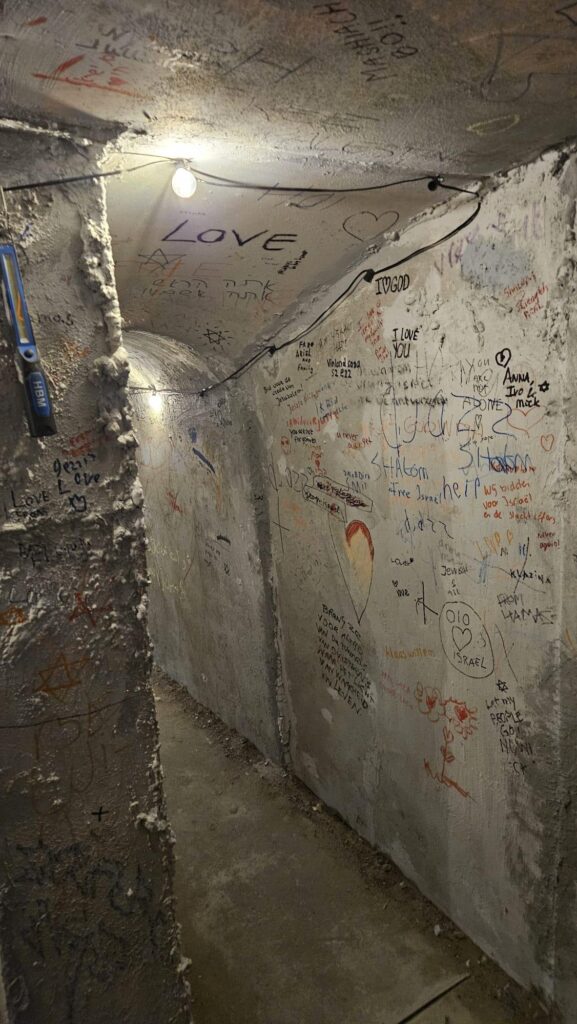

The tunnel is designed to recreate the conditions that hostages endure. The materials were carefully selected to resemble the real tunnels. The soundscape, created with eight hidden speakers that make the bombings seem to come from all directions, uses real recordings of bombings in Gaza. A perspective painting gives the illusion that the tunnel continues for kilometers. In addition to this realism, the walls are covered in messages. The public is encouraged to write on them, with messages such as ‘get them home,’ ‘free the hostages,’ ‘peace,’ ‘come quickly Lord Jesus,’ and even ‘Urk.’

The ‘Hamas tunnel’ is a multimedia installation intended to provoke emotion and aims to raise awareness about the fate of the hostages. It’s part of a broader series of cultural initiatives seeking to highlight their plight. For example, in the United States, there is an immersive media exhibition titled ‘06:29 AM: The Moment Music Stood Still’ which tours the country. Visitors walk through a set with items from the Nova Festival, including burned-out car wrecks and belongings left behind by fleeing festivalgoers. Through video installations, visitors virtually experience the attacks. The creators hope to generate more empathy for the hostages this way.

In Israel, there are also multiple initiatives highlighting the hostages’ situation. In a square in front of the Tel Aviv Museum of Modern Art, various multimedia works depict the hostages' fate. The square, known as ‘Hostages Square’, features permanent installations. For example, there’s a seder table with empty chairs for the hostages. On the same square stands the aforementioned tunnel replica. Roni Levavi, the artist who built the tunnel, says he doesn’t want to make a political statement: "I’m an artist; politics doesn’t interest me. I just want the prisoners to come home." Hostages Square is the site of deep disagreements: for some, the hostages’ plight justifies military interventions, while others call for negotiations, prisoner exchanges, or peace. In Israel, the issue of the hostages is deeply divisive, and art plays a role in highlighting, channeling, and evoking emotion.

This makes such initiatives important subjects for research. Within our research project MAKEBELIEF, we study how immersive media are used to convey messages and how audiences experience these attempts. We use the concept of ‘imagineering’—a combination of imagination and engineering—which means using media techniques to guide people’s imagination. We explore how museums, theme parks, and immersive exhibitions use techniques to make us feel something. This includes how genocide, war, and conflict are portrayed.

A key challenge of imagineering is the difficulty of controlling how the audience feels. You can provoke emotion, but who says it’ll be the desired emotion? We encounter this in the artworks, museums, and parks we study. The same goes for the ‘Hamas tunnel.’ The creators aim to evoke compassion for the hostages. But the same tunnel can also signify other things. As I stood in that claustrophobic tunnel, hearing the sound of bombing outside, I thought about how tunnels can also offer protection from the violence above. With images of a destroyed Gaza in my mind, Gaza’s population comes to mind..

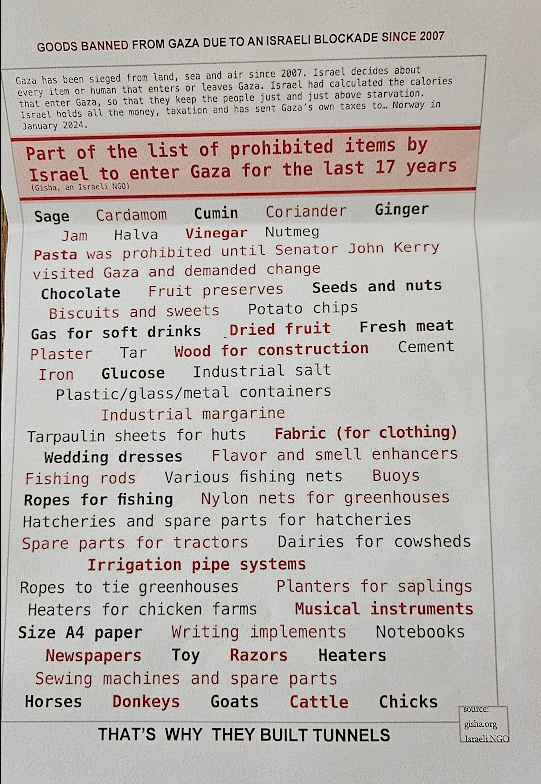

The tunnel's meaning is also contested outside. Protesters against the tunnel shout slogans like ‘Zionism is fascism’ and ‘Stop the genocide.’ Police push back the few dozen protesters and strike forcefully. Two protesters cling to the doors of the Maagdenhuis. Two others spread out a small rug and lay out various food items—tea, pasta, and spices. A flyer explains that due to blockades, such goods have barely entered Gaza since 2007. Tunnels are a way to transport essential goods. The everyday nature of these items offers a tangible argument that the tunnel has meanings beyond being a prison for hostages. The flyer concludes: ‘That’s why they built tunnels.’

Coincidentally, later that afternoon at the Spui25 debate center, a symposium on famine takes place. Speakers emphasize that famine is not a natural phenomenon, but a political one—resulting from decisions, policies, and geopolitics. Gaza is cited as a contemporary example: bombings on ports, food distribution networks, and border crossing blockades have created the fastest-escalating famine in modern history. Again, the tunnel becomes a powerful symbol: the tunnels under Gaza are part of an infrastructure shaped by war and hunger.

In supporting their assessment that genocide is taking place in Gaza, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch extensively discuss the role of the tunnels. The organizations show how the tunnels are used as justification for military actions, and how operations targeting the tunnels have far-reaching effects in Gaza, including on infrastructure, heritage, and the water supply.

In this way, on this single afternoon at Spui in Amsterdam, a struggle over the meaning of ‘Gaza’ and its tunnels unfolds in multiple ways. It shows how the war in Gaza is a site of intense emotional polarization: emotional framing determines which lives are mourned or not—what philosopher Judith Butler calls ‘grievable lives.’ This framing emerges through a wide range of cultural practices. In journalism, during protests, in NGO work, and on social media, a battle for the emotional attention of the public rages on. And even in ordinary public squares like Spui in Amsterdam, this battle takes place. It’s a subject that researchers like us must also engage with: how is compassion stirred, and by and for whom? What is the political role of emotion, and how do media contribute to evoking it?

The video below offers an impression of the 'Hamas tunnel.' It was shot in 360-degree footage. You can look around by moving your phone or dragging with your cursor: