“With its panoramic ceiling, sound effects, and three-dimensional elements, the museum allows visitors to experience the excitement of the conquest of Istanbul every day of the year.”

This is how Panorama 1453 Museum introduces its 360° panoramic reenactment of the Ottoman conquest of Istanbul. Why would a historic war that was fought more than five hundred years ago still evoke excitement today? The fall of the Byzantine capital to Sultan Mehmed II on 29 May 1453, after a fifty-three-day siege, is considered an important historical event that figures greatly in the shaping of national, religious, and neo-imperial identities in the Turkish Republic. Since the early 2000s, there has been an ever-increasing emphasis on the conquest and other major historical events from the Ottoman imperial period in Turkish domestic politics and foreign policy, particularly with the rise of the conservative AKP government. Under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s rule, Turkey has been promoting a neo-Ottomanist ideology, which aims to revive the country’s Islamic and Ottoman legacy and challenge the nationalist and secularist framework of Kemalism. This shift toward neo-Ottomanism is also reflected in Turkey’s cultural heritage policies and sectors. Over the past two decades, numerous cultural events, museums, television programs, and art exhibitions have celebrated “the Ottoman heritage” (Osmanlı Mirası) as a legacy predating the Republic that was once neglected but is now being embraced again.

For many adherents of neo-Ottomanism, Istanbul’s conquest was a moment of pride, a milestone not only in the history of the Turkish nation but also in global history. Historiography lessons in Turkish primary and secondary schools teach about the conquest as a seminal event that marked the end of the Middle Ages and ushered the world into early modernity. Another common view in Turkey regarding Istanbul’s conquest is that it fulfilled an Islamic prophecy attributed to Prophet Mohammad. Many cite a famous hadith in which the Prophet foretells the capture of Constantinople and praises its commander: “Surely, Constantinople will be conquered. What a wonderful army that conquering army will be, and what a wonderful commander that conqueror will be.” The hadith is regarded as evidence of how Sultan Mehmed II’s victory over the Byzantines was pivotal for the Islamic world and how it should be a source of pride for the Muslim Turkish nation.

Such glorified imaginaries of Istanbul’s conquest, as both national and religious achievement, are central to the Panorama 1453 Museum’s narratives. The official website of the museum chooses to contextualize the capture of the Byzantine city as “an event that changed the course of history… [and] brought a new order to the world.” The museum also devotes ample space to exploring the conquest’s connection to the Prophet’s hadith. Before entering the panoramic exhibit, the text panels that welcome visitors explain how Sultan Mehmed II was deeply invested in fulfilling the Islamic prophecy. They present the conquest as an event that was destined to happen and celebrate its religious significance as an Ottoman victory.

Modes of Learning and Modes of Experiencing

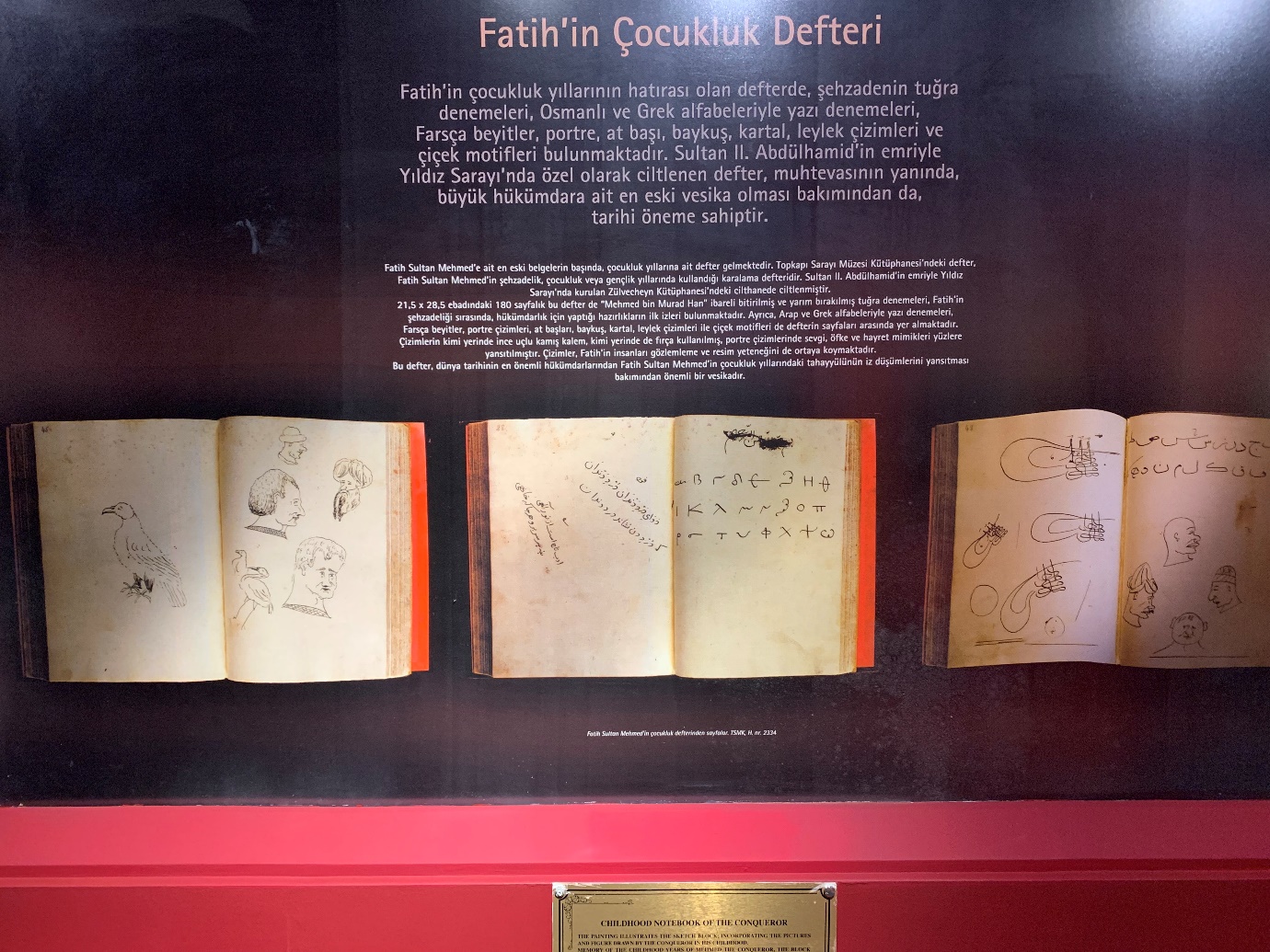

Like many other panoramic exhibits in Turkey, the Panorama 1453 Museum intentionally separates learning from experience. It achieves this by creating two different spaces that elicit different modes of engagement in visitors. The first space features text-heavy panels, a bronze statue of Sultan Mehmed II on horseback, printed replicas of his portraits, images of his swords and caftans, and a miniature model of the panoramic exhibit. The purpose of this room is purely informational. The narratives on the panels are didactic and rather dull. If the visitors can push past the dullness and read the texts, they may learn about Istanbul’s history, Sultan Mehmed II’s childhood, years in the madrasa, and his relationship with his mentors, Molla Gürâni and Akşemseddin. Printed images of the sultan’s childhood notebook showcase his attempts at calligraphic signature (tuğra), his handwriting in Ottoman and Greek, and drawings of animals like storks and horses.

A few text panels explain the military strategies that made Istanbul’s conquest possible, from the construction of the Rumeli Fortress to the Sultan’s order to transport sixty-seven ships over land to the Golden Horn area. Glory is at the forefront of all of these narratives: the heroism of the Ottoman soldiers, the advanced military technology, and Sultan Mehmed II’s wit in outsmarting the Byzantine army. However, certain details are missing. Those are the less glorious facts about the conquest. Take, for example, the presence of 1,500 Christian cavalrymen from the Serbian Kingdom of Rascia, who fought alongside the Ottoman army against the Byzantines, or several accounts that talk about how lootings took place after the fall of the besieged city. The museum does not include such details in its narrative. Instead, it presents a monolithic, mythical, and romanticized imagery of Ottoman victory, emphasizing how this historical event has had unparalleled significance for Turkish history, the Islamic world, and beyond.

After the textual setup, the visitors are finally led upstairs via a curved black staircase to the panoramic reenactment space. This rotunda-shaped room is starkly different from the one downstairs. There are no texts or audio voiceovers that explain the conquest; instead, the exhibit seeks to immerse visitors in a multisensory experience of it. The impressive dome, measuring 38 meters in diameter and 14 meters in height, serves as the backdrop for a 2,350-square-meter three painting that animates the Ottoman army’s final assault on the Byzantine city walls on May 29. The painted scene includes over ten thousand figures. Hundreds of Ottoman soldiers are seen attempting to scale the walls using ladders. Several towers of the city walls are set ablaze by the successful cannon fire from the Ottomans. The renowned Ottoman soldier Ulubatlı Hasan is depicted raising the Ottoman flag on one of the towers, just moments before his death from arrow attacks. The Byzantine army is portrayed pouring burning oil from the walls to halt the advancing Ottoman soldiers. Soldiers are seen loading barrels onto mules in the grassy fields surrounding the city walls while others fire cannonballs at the walls.

Between the painting and the circular deck designated for visitors, there is a transition area where life-size maquette models of cannons, gunpowder barrels, cannonballs, arrows, and shields are scattered on the ground. This front stage is designed to appear as if it is an extension of the base of the panoramic canvas. The maquette models help create an illusion of a continuous three-dimensional battlefield, where the visitors can feel like they are part of the scene. The technique of blending these different media forms into one another certainly makes the experience of Istanbul’s conquest more immersive and visually convincing. Sound effects also contribute to the immersive atmosphere of the panoramic exhibit. The booming cannon fires, the clash of swords, the shouts, grunts, and cries of soldiers, and the chants of Allahu Akbar blend with the continuous playing of the Ottoman military band songs (mehter), which was meant to boost soldiers’ spirits. These audio sensory elements complement the visual spectacle of the rotunda’s paintings and the maquette models of weapons.

All in all, the Panorama 1453 Museum is a striking example of how history is not only narrated but also staged, reanimated, and experienced through cultural heritage spaces designed for immersivity. The different modes of visitor engagement in the two rooms—the text panel room and the panorama room—are particularly striking. One is designed to engage visitors’ intellect, aimed at enhancing their knowledge of the conquest, while the other focuses solely on stimulating their senses, providing them with an experience. Standing on the circular platform beneath the painted sky, surrounded by the echoes of battle and lifelike visual effects, visitors feel as though they are part of the battle scene between the Ottomans and the Byzantines. The need for immersivity at museums like Panorama 1453 reflects a broader ideological shift in Turkey, with the rise of neo-Ottomanism, where history is deployed as more than a narrative. Instead, it becomes an affective performance, in which the senses and the body become integral to the shaping a historical event with techniques of staging and animating.

You can get a glimpse of the experience of Panorama 1453 through the YouTube video below. (Note: The video is recorded in 360 degrees, so you can look around by moving your phone or dragging with your cursor.)