Background

In the beautiful South Limburg village of Valkenburg aan de Geul lies a remarkable national monument, the Museum Romeinse Katakomben (Roman Catacombs Museum, with the archaic spelling used intentionally). The average person may quickly imagine what this entails: present-day South Limburg was an important food-producing region during Roman times, so it seems plausible that the Romans would have used the soft, easily worked marlstone to carve out some burial sites.

But that’s not what the Catacombs are. In fact, the caves in question were originally only carved out as a marlstone quarry in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1908, in the context of the Catholic Emancipation Movement and Pillarisation, the wealthy Tilburg textile manufacturer Jan Diepen decided to have the tunnels of an old quarry converted to assert himself as a patron of the arts and to expand the Catholic heritage of the region. As a devout Catholic and a lover of Roman archaeology, his choice was quickly made. He was inspired by the early Christian Catacombs under Rome.

The original

Beneath the city of Rome, dozens of different cave complexes have been found, most of which have Christian origins from before the time of Constantine and Theodosius, during the period when Christianity was still forbidden in the Roman Empire. The polytheistic Romans generally practiced cremation and had no need for underground tombs. However, Christians of that time believed that the body would still play a role at the End of Days and therefore could not be destroyed. The Catacombs of Rome had the added advantage of being underground, making them less likely to be discovered and destroyed. Christians were persecuted for their faith and often killed. A significant portion of the graves from this period are dedicated to martyrs, Christians who died while holding onto their faith.

After the end of Christian persecutions, the Catacombs gradually lost their function as hiding graves and took on a new role as pilgrimage sites. The early Christian community and the martyrs who died for their faith were canonized as saints. People visited the graves seeking to come into contact with the sanctity and devotion of the martyrs, and to partake in it. During this time, many relics were also removed from the graves. After the end of Christian persecutions, the Catacombs gradually lost their function as hiding graves and took on a new role as pilgrimage sites. The early Christian community and the martyrs who died for their faith were canonized as saints. People visited the graves seeking to come into contact with the sanctity and devotion of the martyrs, and to partake in it. During this time, many relics were also removed from the graves.

Between Archaeology and Devotion

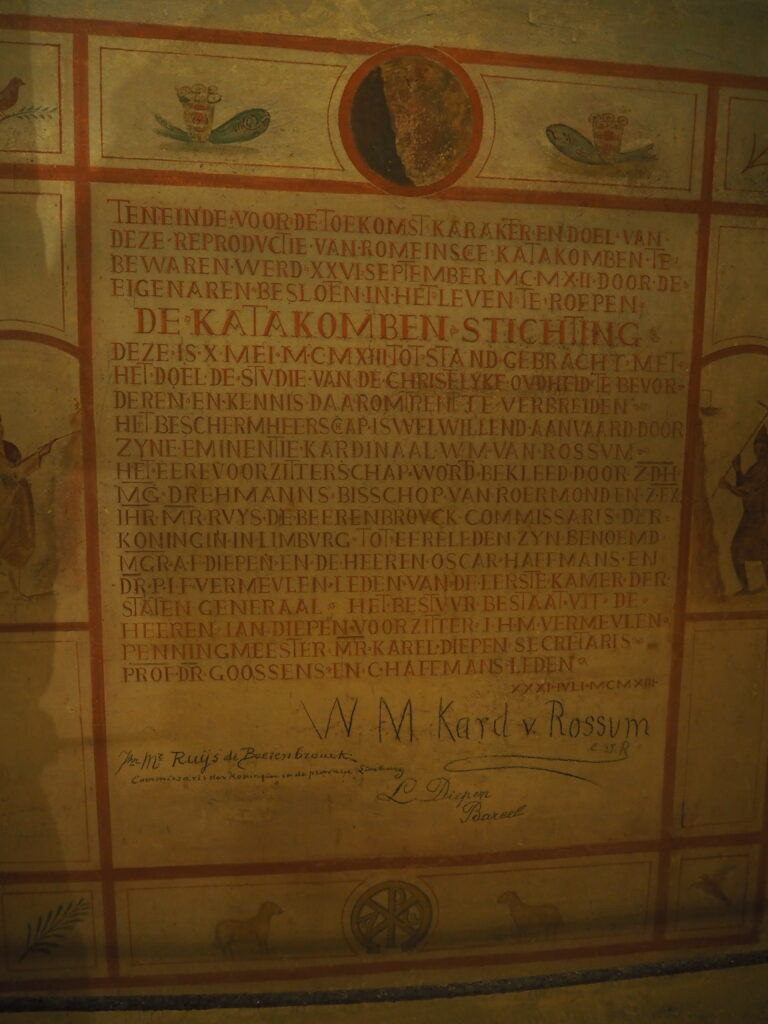

The Valkenburg Catacombs are officially primarily an archaeological, scientific, and educational museum project, made in collaboration with non-believers and Protestants, and designed with them in mind. However, it’s undeniable that a strong Roman Catholic identity is embedded within it. The choice to specifically replicate this Catholic-Christian heritage clearly stems from the Roman Catholic background of the patron. The project was created with the personal approval and blessing of Pope Pius X, and plaques on the walls commemorate visits from bishops and other church authorities who have visited the museum over the years and bestowed their blessings.

Over the years, the tour through the tunnel system hasn’t always been “neutral.” From the opening, the guides took into account the religious beliefs of their visitors, making adjustments to the tour based on their background (for example, omitting mentions of the Pope, Mary, and the Sacraments). Due to the preferences of guides, visitors, Catholic clergy, and non-Catholic critics, the museum quickly took on a Catholic character.

Ultimately, for Roman Catholics, the Catacombs have an additional devotional significance that is not relevant to other visitors. In the imaginary “world” of the Catacombs, these groups experience two slightly different roles. A Catholic visitor might feel the closeness of Rome, the center of faith, and the (symbolic) presence of the holy martyrs. They might imagine what it’s like to be a pilgrim in underground Rome. For the Protestant or non-Christian visitor, who doesn’t believe in the importance of these saints, the attraction might be less spiritual. Such visitors likely imagine themselves more as archaeologists or explorers, searching for knowledge or treasures from the past. During the tour itself, many aspects still evoke a sense of devotion. Until a few years ago, flashlights weren’t used during the tours, as is customary in marl caves. Instead, each visitor received a small candle and walked through the tunnel system in a sort of procession. Due to safety concerns, these candles were recently replaced by two electric lamps.

Authenticity

The Catacombs also raise an interesting question about “authenticity.” None of the Roman artworks depicted in the museum were made in antiquity. The layout of the tunnel system is also largely fictional: the Valkenburg complex contains several burial chambers. These are replicas of the most beautiful and significant graves beneath Rome. The chambers are connected by narrow passageways with anonymous burial places of less affluent people in the walls.

However, the layout of this tunnel system is not authentic at all (in Rome, the catacombs are often located in multiple, unconnected tunnel systems), and there was also a deliberate choice to combine only the finest examples in replicas. At the same time, there is an effort not to beautify the truth. In places where the art was damaged in 1908, corresponding “damage spots” were also added to the replicas. Clearly, there was a lot of thought about what creative liberties were acceptable and what might come across as tasteless or fake. The creators of the Catacombs wrote about this in their 1916 commemorative document:

"Every reconstruction is a lie – that cannot be denied. But hasn’t the openly acknowledged lie shed the sting of inauthenticity? Valkenburg wants to honor Rome, not imitate it. To reach but not surpass. It seeks to transfer the age-old Christian piety into its own soft soil."

So, the question of authenticity isn’t just about accurate imitation. The desire to “respect” the original also plays a role.

More than a hundred years after its opening, and despite strong secularization, the Catacombs are still open to the public. The stream of Roman Catholic devotional visitors has significantly dwindled. The museum now has to survive in modern, secular, and pluralistic 21st-century Netherlands. For modern visitors, the emphasis is on the historical aspect. It’s a place where you can learn something about ancient Rome.

Still, the museum retains an appeal that evokes a certain kind of spirituality. The caves are used by practitioners of wellness and Eastern spirituality. During my most recent visit, I had the honor of being accompanied by two English mediums from Newcastle who were visiting special burial sites in hopes of encountering spirits. They were disappointed to learn that no one was actually buried in the Catacombs, as that meant no Roman spirits could be wandering there. Despite the lack of ghosts, they were critical yet enthusiastic visitors. Though no one in our group was a practicing Catholic, we had a diverse group of visitors from different religious contexts, and the frescoes and stories sparked fascinating conversations about norms and values in our culture and those of ancient Rome.

The Valkenburg Catacombs are a unique place. They take you simultaneously to Rome in 300 AD and the early 20th century. If you’re lucky, your fellow visitors might even take you along on their own 21st-century spiritual journey.

Source: “The Roman Catacombs in Valkenburg aan de Geul, the story of a unique copy” (2015), available in the museum shop.